History of the Clean Water Act

Rivers, streams, wetlands, estuaries, lakes and bays are considered surface waters. Following the start of the American Industrial Revolution – circa 1970 – our rivers were treated as sewage treatment plants. Our residential, commercial and industrial wastes were directly discharged into rivers under the assumption that the pollutants would be naturally cleaned/absorbed as the rivers carried them downstream.

In 1969, the Cuyahoga River in Ohio caught on fire. Let that sink in: a river caught on fire. The volume of pollution had become so high that rivers could no longer naturally treat our discharges, and industrial waste directly led to this conflagration. As a result, the Clean Water Act was passed in 1972.

Water bodies can receive two types of pollutant discharges: point source pollutants and non-point source pollutants. Point source pollutants are direct discharges from industrial facilities, such as waste water treatment plants, refineries, mines, manufacturing facilities, etc. Think of it this way: point source pollutants are defined by a specific geographic point – in latitude and longitude – where pollutants are entering a water body. This point usually is in the form of a culvert or outfall. This category of water pollution is a problem in Lavaca Bay.

NPDES Permits, Toxic Release Inventory, and the ECHO database

The Clean Water Act forbids the discharge of regulated point source pollutants into Waters of the United States – streams, estuaries, bays and sometimes wetlands – without a permit. The National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) is the permitting system that industries must use in order to legally discharge waste waters. In Texas, this system is managed by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) and is called TPDES.

Formosa Plastics has an expired but new pending TPDES permit for its facilities at Point Comfort (Permit Number WQ0002436). The former permit covered the release of ‘trace’ amounts of plastics into Lavaca Bay via outfalls (01, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 13). The new proposed permit is requesting zero discharge of plastics via the outfalls 01, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12 and 14. Outfall 01 discharges directly into Lavaca Bay and stormwater outfalls 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12 and 14 discharge into Cox Creek. Outfall 13 discharges into Cox Bay and outfall 11 discharges into Lavaca Bay via Formosa’s loading dock.

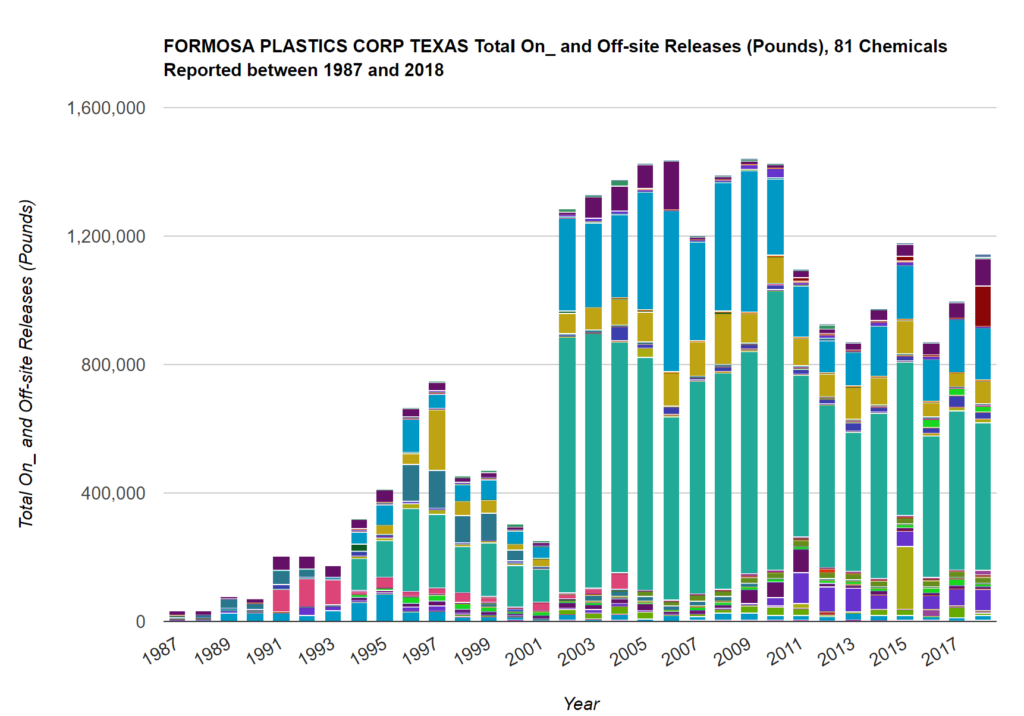

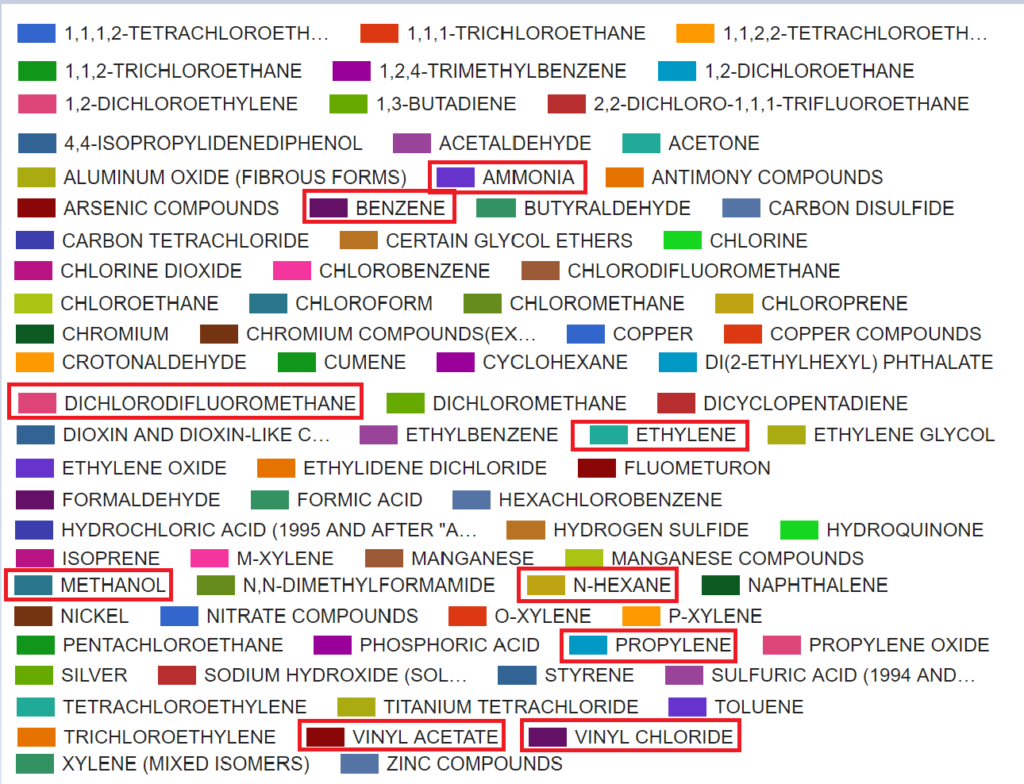

According to the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) Facility Report for the Point Comfort facility, Formosa Plastics has been releasing a variety of compounds into Lavaca Bay through a combination of point source discharges via these outfalls and air emissions via flares.

The EPA’s Enforcement and Compliance History Online (ECHO) database lists Formosa as being in noncompliance with their NPDES permit 6 out of 8 of the last quarters. In other words, over the last 3 years (as of May, 2020), 75% of the time that the TCEQ has inspected the facility, Formosa has been in violation of the Clean Water Act. SABEW, of course, has found the facility to be in violation of the Clean Water Act 100% of the time based on our daily pellet surveys.

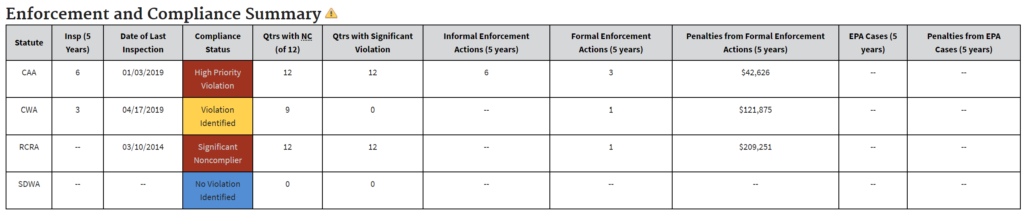

Beyond water discharges, the ECHO database cited above also lists Formosa Plastics as being a chronic Significant Noncomplier of the Clean Air Act (CAA) and the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA) since 2004. RCRA is a federal law that regulates the proper management of hazardous and non-hazardous solid waste – this includes generation, transportation, treatment, storage and disposal of hazardous waste. Unlike the NPDES system, CAA and RCRA compliance is overseen by the EPA.

Together, all of these violations paint a picture of an industrial facility that is not managing its outputs responsibly. As a response, the State and Federal governments should have significantly intervened at this point; yet, until the SABEW lawsuit, there had only been minor fines. Formosa Plastics has been chronically and continually polluting Cox Creek, Cox Bay, Lavaca Bay, and Matagorda Bay, the surrounding airshed, and it potentially has a much larger chemical pollution footprint when RCRA is considered.